The Legacy of Dr. Amy Louise Brown

by Patricia J. Flowers, College of Music, Florida State University

Miss Amy L. Brown received a letter from FSU College of Music Dean Wiley Housewright in May 1974 offering her a position as assistant professor of music to begin that fall. The letter was addressed to her home in Palisades Park, NJ, across the George Washington Bridge from Teachers College, Columbia University, where she was pursuing the Ed.D. specializing in elementary music. She accepted the job just two days after it was sent and prepared to move to Tallahassee. Her professional background and strong recommendations made her a good candidate for the position at Florida State. She had taught piano for some 25 years and was employed as a public school general music teacher in New York and New Jersey during the early 1970s. The principal at one of her schools wrote that Amy was an excellent teacher, creative in her work, and a skilled musician who inspired children with a love of music. Dr. R. Douglas Greer, her doctoral adviser at Teachers College (TC), Columbia University, wrote that she was “bright, scholarly, and dedicated.” Although she joined the FSU faculty before finishing her doctoral dissertation, she received support from mentors at both Teachers College and FSU allowing her to complete the Ed.D. two years later in 1976. She arrived in Tallahassee at a pivotal point in time as the School of Music and the university at large were actively seeking to rise in stature and increase diversity. Dr. Brown contributed to both goals as a member of the FSU music faculty. In 1974, she was only the 7th black professor hired at Florida State University, then upon promotion five years later, she became the first tenured African American faculty member in the School of Music. Her reputation grew as a beloved teacher who championed high standards, personal responsibility, and inclusion of all people. Her family background, innate talent, scholarly activity, personal convictions, and community of colleagues contributed to her success and to the gifts that she returned to FSU and the music education profession.

Born in 1930, Amy Brown grew up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania within a family that valued hard work and education. Her grandparents, Amy and Cornelious Brown, had moved to Pittsburgh from rural South Carolina to seek new opportunities. Granddaughter Amy respected her forebears and was especially close to her grandmother who was known as Mom Brown. She learned from her grandparents that “Your life is to be a light to shine on others,” “You have to stand up for yourself,” and “If you want it, believe it.” Amy’s mother, Modlee Swan (Ol’ Miss), worked long hours to provide Amy with the early experiences, values, and education she needed to be successful. As a young child, Amy would pretend to play the piano and make up tunes, so her mother got her a toy piano to encourage this interest. She eventually took piano lessons on a real instrument and played at church and school. She became quite accomplished and years later her sister-in-law, Armetta Swan, remembers Amy playing Beethoven at church when they were young. A family story recalls a time when Amy needed a recital dress and demonstrates her mother’s honesty in repaying a debt. As a professor, Dr. Brown would sometimes tell this story to students to exemplify the virtues of responsibility, perseverance, and ethical behavior. In the words of Dr. Brown’s mother,

It was the day before the concert and I needed $3.00 to get this little dress out of layaway for Amy. …There was an Italian restaurant on the second floor and the shop was on the first floor. I knew I had to have that dress and I hated to go begging, but I didn’t have a choice. I kept walking past the shop and finally I went in. A lady had the store. I told her that I needed that little dress for tomorrow so Amy could wear it to the concert. ‘I know I’m supposed to give you three more dollars,’ I said, ‘but I don’t have the money. If you will let me take the dress today, I will stop by every day and give you a dollar until the dress is paid for.’ I sat down with her and went over everything – that I worked for a house on Mellon Street and I earned three dollars a day. I told her I would stop by her shop first before going home and pay her one dollar until the dress was paid for. She wrapped the dress up and gave it to me. I stopped by every day and gave her the money. After that, if I needed anything, she would let me have it.

Thus, young Amy learned about appropriate behavior at the same time she grew in musicianship. Not only did she become a fine pianist but she also played the flute for some ten years. She and her brother Sonny started a choir at their high school in 1949 that became the successful Swan Chorale which remained active under Sonny’s leadership for nearly 60 years. Even after she went off to college, Amy would return to Pittsburgh to work with her brother in community musical and educational programs. Thus, the foundations were set for her career that combined musicianship, education, and outreach.

Following high school graduation, Amy Brown attended Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh, now known as Carnegie Mellon University. She later transferred to Oberlin College, and ultimately graduated with the Bachelor of Music degree (Mus. B.) from Boston University in 1963. She received piano scholarships at all three of these institutions. Her life took an interesting turn after completing the baccalaureate degree in Boston. Not only did she teach piano lessons throughout this period, but also became a cytologist, working in hospitals and laboratories in the Boston and New York City areas. Her work appears to have been well-respected as she and her colleague, Virginia Lerch, were formally acknowledged in a peer-reviewed medical journal for their assistance in a research study. During this time Amy became close with the Bloom family who ran a laboratory in Needham, Massachusetts. Their daughter, Leslie Bloom, recalls growing up knowing Amy as a friend, role model, and confidant. Amy shared trips with the Bloom family to Tanglewood Music Festival, the Apollo Theatre, and the Village Vanguard, along with visits to art museums and many conversations about music and life. Now a professor herself, Dr. Leslie Bloom says she still thinks of Amy when she is making a decision: “Always do the right thing. Keep your ethics.” These early messages became recurring themes throughout Dr. Amy Brown’s years as an FSU professor.

Amy Brown led a full life as a piano pedagogue, cytologist, and elementary school music teacher prior to entering TC-Columbia where she earned the M.A. degree in 1971 and stayed on to pursue the doctorate. Her adviser, Dr. R. Douglas Greer, remembers her as a bright and insightful graduate student; a connoisseur of cultural events, especially classical music, jazz, and dance; and “a real lady with a steel core.” He supported her move to Tallahassee in the fall of 1974 where she ultimately drew upon her family background, early experiences, and educational achievements in fulfilling her dream job at Florida State University.

As a faculty member at FSU, Dr. Amy Brown taught classes in elementary music methods; orientation to music education (co-taught with music education/therapy colleagues); introduction to graduate studies in music; and social and historical foundations of music education. There was a period during which she traveled to the Panama City campus weekly to teach elementary music methods for education majors, and she spent the fall semester of 1994 teaching music appreciation for FSU International Programs in London. She was known to be demanding in the classroom but also inspiring and supportive. Her successful approach to instruction was recognized when she received a University Teaching Award in 1988-89.

While her teaching assignments remained consistent over the years, Dr. Brown’s service load grew to a large proportion. One possible reason was the need for women’s and minority voices on university governance committees, but it is also clear that she was willing to serve the university to the best of her ability, regardless of whether she was filling a role. Many of her service commitments focused on student services, mentoring, undergraduate policies, and grievances. These contributions are consistent with her research interest in student advisement and degree persistence. She had a philosophical bent and consistently made transfers from research to teaching about music and life. One of her oft-quoted research findings was that “knowing is not valuing.” Over the course of her career, she expected students to bring knowing and valuing into alignment. For her, teaching, research, and service were not discrete categories but domains ideally applied to a way of living that linked thinking, valuing, and acting.

Dr. Brown’s former doctoral advisees remember her as a steadfast friend and mentor. From her first dissertation advised in 1986 to the last in 2002, Dr. Brown’s Ph.D. students reflect on her unflagging insistence on good writing and careful choice of words. They also comment on her calming presence, sense of humor, and generosity. Dr. Diane Orlofsky said that “She was a model of scholarship, communication, meta-cognition (thinking about thinking), and plumbing the depths of who you are. She set a model, an example, a standard.” Dr. Brown’s teachings live on in the good work of her former students.

When asked to speculate on what Dr. Brown would say about being the first tenured African American faculty member in the College of Music, most agree that she would likely downplay that role. She was an outspoken advocate for the education of all people and was equally supportive of students who represented many different forms of diversity and individuality. Nevertheless, we may acknowledge the inherent leadership of being a “first” and respect her strength in upholding her grandparents’ charge to be a light, to stand up, and to “believe it.” Even though not commented upon directly, surely there were many students over the years who looked at Dr. Brown and saw something of themselves in her quiet countenance.

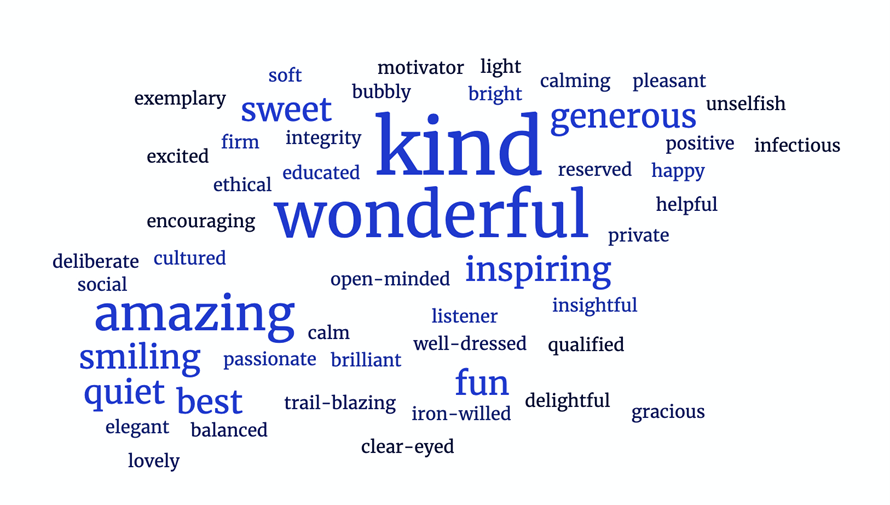

Dr. Brown submitted a letter to Jon Piersol, Dean of the College of Music, in September 2001 informing him of her intention to retire at the end of spring term 2002. She wrote, “…I find little joy in conveying the formal advice of this letter to you; our School of Music is such a wonderfully encompassing place.” She had indeed achieved her dream job and made a difference to FSU students, the university, and the profession during her 28 years of employment. During retirement she visited friends and family, traveled nationally and internationally, attended cultural events, and went shopping. Her passing on June 4, 2020 in Tallahassee was marked by an outpouring of heartfelt social media comments from many friends, colleagues, and loved ones who were privileged to know her. While every expression had individual meaning, there were certain personal adjectives that resonated throughout the tributes. The following word cloud shows how people described their dear friend and mentor. May her goodness long be remembered.

Sincere thanks are extended to those who contributed to this article, including Leslie Bloom, Alice-Ann Darrow, John Geringer, Douglas Greer, Mary and Clifford Madsen, Diane DeNicola Orlofsky, Fred Spano, Jayne Standley, and Armetta Swan.

Papers presented by Amy Brown at the International Symposium on Research in Music Behavior, 1980-2001:

A predictive instrument for prospective music teachers: Year one of a four-year study. New York City, 1980.

First term teaching and grades as predictive measures for success of prospective teachers: Year three of an ongoing study (with Jayne M. Alley [Standley]). Tallahassee, 1982.

A model for personal evaluation. Fort Worth, 1985.

Music teachers’ ability to transfer personal philosophy to teaching. Logan, Utah, 1987.

The perceptions of pre-interns and professional music teachers concerning three knowledge-based criteria: Preparation and planning, teaching, and personal characteristics. Baton Rouge, 1989.

Prospective teachers’ self-concepts and perceptions of teaching. Cannon Beach, Oregon, 1991.

A model for personal evaluation: Music education majors self-assess teaching skills attainment and delineate acquisition plans. Tuscaloosa, 1993.

The Florida State University doctoral program in music education: The ethnology of a culture. Granville, Ohio, 1995.

Thinking about one’s thinking: Pre-service teacher perceptions of reflective thinking. Minneapolis, 1997.

Preservice teachers observe and reflect upon music teaching in elementary school. Montreal, 1999.

Music education prospective doctoral degree candidates reflect upon Bennett Reimer’s essay concerning why humans value music. Fort Worth, 2001.